Text encoding

We have covered how to represent numbers in binary; in this section we’ll explore representations of text as bits. By “text,” we mean alphabets and other writing systems — used everywhere from status updates and text messages to email and digital books.

1 Beginnings

To begin, we can propose a way of mapping letters and other characters

(punctuation, space, etc.) to numbers. For example, let A be

represented as the number 0, B as 1, C as 2, and so on. There are

26 letters in the English alphabet, so Z is 25, and we’d need a

total of 5 bits. (25 = 32, so we’d even have a few numbers left over

for punctuation.)

Exercise: using the scheme outlined above, decode the word represented

by the bits 00010 00000 10011

Show answers

If our text messages need to distinguish between upper- and lower-case letters, we’ll need more than 5 bits. Upper-case A–Z is 26 characters, lower-case a–z is another 26, so that’s a total of 52. 26 = 64, so 6 bits would cover it and again have a few available for punctuation.

But what about including numbers in our text? If we want to send the

text message “amazon has a 20% discount on textbooks,” we can’t really

represent that “20” as 10100 in binary, because that would conflict

with the representation of the letter U.

Instead, we need to add space for the standard ten numerals as characters. Including those with upper- and lower-case letters means we need at least 62 characters. Technically that fits in 6 bits, but we’d have very little room for punctuation and the character representing a space. So for practical purposes, we’re up to 7 bits per character. 27 = 128, so now there is a good deal of room for other symbols.

As an aside, there could be a way to “reuse” alphabetic

representations as numerals. We’d just have to precede them with a

marker that means “this is a number,” or else require the recipient to

guess from context. This is the situation in Braille — a writing

system for people with visual impairments — that is based on 6-bit

characters. (Each of six locations can be raised or not.) The Braille

character for A is the same as the number 1.

2 Fixed vs variable-width

The simple encodings I proposed in the previous section are based on a fixed number of bits per character — whether it is 5, 6, or 7. One way to illustrate that is as a tree — see figure 2.

Trees are a commonly-used data structure in computer science, but they are a little different than the organic trees to which they refer. First of all, we usually draw trees with the root at the top, and they grow down the page. Each time a circle splits into two paths, we call that a branch. The tree ends at the bottom with a row of leaves.

This particular tree is a binary tree, meaning that every node is

either a leaf, or a branch with exactly two children. The nice

thing about a binary tree is that paths from root to leaf correspond

exactly to binary numbers. Just think of zero as going left in the

tree, and one as going right. Then, the number 01101 (for example)

corresponds to left-right-right-left-right, which lands on the leaf

marked N.

Exercise: decode these text messages using the tree in figure 2.

10000111110000000101101000110111110001100000001100001001101001110101010010010001

Show answers

You can tell the previous tree is fixed-width because every path from root to leaf is exactly 5 transitions. Now compare that to a variable-bit tree, in this file:

In this case, different letters can have very different numbers of bits

representing them. For example, E is the shortest path, representing

just 3 bits. X is a very long path, representing 10 bits.

Unlike with the fixed-width encoding, it can be tricky to tell where one letter ends and the next letter begins. You simply follow the path in the tree until you land on a leaf. Then, start again at the root for the next bit.

Exercise: decode these text messages using the Huffman tree in figure 3.

0010010000011100111110111111111101100111000111010011001111010011010100010010000010000

Show answers

This particular variable-width tree is crafted so that the overall effect is that it compresses English text. This works because more commonly used letters are represented with proportionally shorter bit strings. For example, let’s compare the encodings using both trees of a sequence of words:

word: fixed encoding: variable encoding:

THE 100110011100100 15 bits 11100001001 11 bits

GRASS 001101000100000 11010000001100

1001010010 25 bits 01000100 22 bits

IS 0100010010 10 bits 01110100 8 bits

GREEN 001101000100100 1101000000001

0010001101 25 bits 0010110 20 bits

SAID 100100000001000 010011000111

00011 20 bits 11011 17 bits

QUUX 100001010010100 1111100001

10111 20 bits 111111111111

1111100010 32 bits

total: 115 bits 110 bits

With the fixed encoding, every character is exactly 5 bits, and so the whole sequence of words is 115 bits. (We’re not counting encoding the spaces between words for this exercise.)

Contrast that with the variable encoding. Nearly every word has a shorter representation. The one exception is “QUUX,” which of course isn’t really a word in English. But it represents the case of a word with infrequently-used letters, and the encoding of that one word increased substantially in size from 20 to 32 bits. On the whole, the second tree still compresses as long as you are mostly using English words with high-frequency letters.

- Video: 5-Hole Paper Tape with Professor Brailsford on Computerphile [9m 45s]

3 ASCII

This brings us to the most popular and influential of the fixed-width codes. It’s called ASCII (pronounced “ass-key”), which stands for American Standard Code for Information Interchange. It was developed in the early 1960s, and includes a 7-bit mapping of upper- and lower-case letters, numerals, a variety of symbols, and “control characters.” Table 1 shows all of them.

| Dec, Hex | Char | Dec, Hex | Char | Dec, Hex | Char | Dec, Hex | Char |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0, 00 | NUL null |

32, 20 | SPC |

64, 40 | @ |

96, 60 | ` |

| 1, 01 | SOH start heading |

33, 21 | ! |

65, 41 | A |

97, 61 | a |

| 2, 02 | STX start text |

34, 22 | " |

66, 42 | B |

98, 62 | b |

| 3, 03 | ETX end text |

35, 23 | # |

67, 43 | C |

99, 63 | c |

| 4, 04 | EOT end trans |

36, 24 | $ |

68, 44 | D |

100, 64 | d |

| 5, 05 | ENQ enquiry |

37, 25 | % |

69, 45 | E |

101, 65 | e |

| 6, 06 | ACK acknowledge |

38, 26 | & |

70, 46 | F |

102, 66 | f |

| 7, 07 | BEL bell |

39, 27 | ' |

71, 47 | G |

103, 67 | g |

| 8, 08 | BS backspace |

40, 28 | ( |

72, 48 | H |

104, 68 | h |

| 9, 09 | HT horiz tab |

41, 29 | ) |

73, 49 | I |

105, 69 | i |

| 10, 0A | LF new line |

42, 2A | * |

74, 4A | J |

106, 6A | j |

| 11, 0B | VT vertical tab |

43, 2B | + |

75, 4B | K |

107, 6B | k |

| 12, 0C | FF form feed |

44, 2C | , |

76, 4C | L |

108, 6C | l |

| 13, 0D | CR carriage ret |

45, 2D | - |

77, 4D | M |

109, 6D | m |

| 14, 0E | SO shift out |

46, 2E | . |

78, 4E | N |

110, 6E | n |

| 15, 0F | SI shift in |

47, 2F | / |

79, 4F | O |

111, 6F | o |

| 16, 10 | DLE data link esc |

48, 30 | 0 |

80, 50 | P |

112, 70 | p |

| 17, 11 | DC1 device ctrl 1 |

49, 31 | 1 |

81, 51 | Q |

113, 71 | q |

| 18, 12 | DC2 device ctrl 2 |

50, 32 | 2 |

82, 52 | R |

114, 72 | r |

| 19, 13 | DC3 device ctrl 3 |

51, 33 | 3 |

83, 53 | S |

115, 73 | s |

| 20, 14 | DC4 device ctrl 4 |

52, 34 | 4 |

84, 54 | T |

116, 74 | t |

| 21, 15 | NAK negative ack |

53, 35 | 5 |

85, 55 | U |

117, 75 | u |

| 22, 16 | SYN synch idle |

54, 36 | 6 |

86, 56 | V |

118, 76 | v |

| 23, 17 | ETB end trans blk |

55, 37 | 7 |

87, 57 | W |

119, 77 | w |

| 24, 18 | CAN cancel |

56, 38 | 8 |

88, 58 | X |

120, 78 | x |

| 25, 19 | EM end medium |

57, 39 | 9 |

89, 59 | Y |

121, 79 | y |

| 26, 1A | SUB substitute |

58, 3A | : |

90, 5A | Z |

122, 7A | z |

| 27, 1B | ESC escape |

59, 3B | ; |

91, 5B | [ |

123, 7B | { |

| 28, 1C | FS file sep |

60, 3C | < |

92, 5C | \ |

124, 7C | | |

| 29, 1D | GS group sep |

61, 3D | = |

93, 5D | ] |

125, 7D | } |

| 30, 1E | RS record sep |

62, 3E | > |

94, 5E | ^ |

126, 7E | ~ |

| 31, 1F | US unit sep |

63, 3F | ? |

95, 5F | _ |

127, 7F | DEL |

The control characters are in the range 0–31 (base ten). They don’t have a visual representation, but instead direct the display device in particular ways. Many of them are now obsolete, but perhaps the most important one is 1010 = 0A16 = 000 10102, which is the “new line” character. Whenever you press enter to go to the next line, this character is inserted in your document.

The character 32 is a space, and 33-63 hold mostly punctuation. The

numerals are at positions 48 through 57. These are easy to recognize

in binary: they all start with 011 and then the lower four bits match

the numeral. So you can tell at a glance that 011 01012 =

3516 is the numeral 5.

The range 64–95 is mostly uppercase characters, and 96–127 is mostly

lowercase. (Both ranges include a few more punctuation characters and

brackets.) These numbers correspond to bit strings starting with 10

for uppercase and 11 for lowercase. The remaining 5 bits give the

position of the letter in the alphabet. So 100 10112 = 4B16 is

the eleventh letter (uppercase K) and 110 10112 = 6B16 is the

corresponding lowercase k.

4 Babel

ASCII worked relatively well for the English-speaking world, but other nations and cultures have needs for different symbols, accents, alphabets, and other characters. It’s impossible to write niño or café in ASCII, or the Polish name Michał, and it’s hopeless for complete different alphabets, syllabaries, or logograms such as the Greek word ἀλήθεια or the Chinese 福.

Computer architectures eventually settled on eight bits as the smallest addressable chunk of memory, known as a byte. Since ASCII was 7 bits, it became possible to use that eighth bit to indicate an extra 128 characters.

This led to a wide variety of incompatible 8-bit encodings for various languages. They mostly agreed in being compatible with ASCII for the first 128 characters, but beyond that it was chaos. Much of it is described in the ISO 8859 specification.

That is, ISO 8859-1 was for Western European languages, 8859-2 for Central European, 8859-4 for North European, 8859-5 for Cyrillic alphabet, 8859-7 for Greek, etc. Sending documents between these language groups was difficult, and it was impossible to create a single document containing multiple languages from incompatible encodings.

As one small example, let’s take the character at position EC16 = 23610. All these encodings disagree about what character it should be:

| Encoding standard | Char | Unicode descriptor |

|---|---|---|

| ISO 8859-1 (Western European) | ì | LATIN SMALL LETTER I WITH GRAVE |

| ISO 8859-2 (Central European) | ě | LATIN SMALL LETTER E WITH CARON |

| ISO 8859-4 (North European) | ė | LATIN SMALL LETTER E WITH DOT ABOVE |

| ISO 8859-5 (Cyrillic) | ь | CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SOFT SIGN |

| ISO 8859-7 (Greek) | μ | GREEK SMALL LETTER MU |

| Mac OS Roman | Ï | LATIN CAPITAL LETTER I WITH DIAERESIS |

| IBM PC | ∞ | INFINITY |

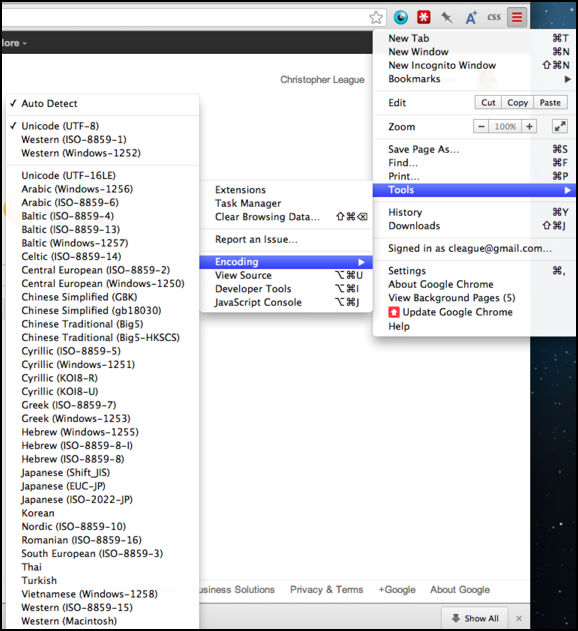

You can still see the remnants of this old incompatible encoding system in your browser’s menu. Most web pages today will be in Unicode — we’ll get to that in a moment — but the browser still supports these mostly-obsolete encodings, so it can show you web pages written using them. Notice that even for the same language, there are often several choices of encodings available.

5 Unicode

To deal with this problem of incompatible encodings across different language groups, the Unicode Consortium was founded with the amazing and noble goal of developing one encoding that would contain every character and symbol used in every language on the planet.

You can get a sense of the variety and scope of this goal by browsing the code charts on the Unicode web site. Each one is a PDF file that pertains to a particular region, language, or symbol system. In total, it’s close to a hundred thousand characters.

The code charts give a distinct number to every possible character, but there is still the issue of how to encode those numbers as bits. Most of the numbers fit in 16 bits, which is why they are expressed as four hexadecimal digits in the code charts (such as 1F30 for an accented Greek iota: ἰ). But 216 = 65,536 and we said there were closer to 100,000 characters, so 16 bits is not enough. Most of the time Unicode is represented as a multi-byte (variable) encoding called UTF-8. The original ASCII characters are still represented as just one byte, but setting the eighth bit enables a clever mechanism that indicates how many bytes follow. Here is a great video explaining Unicode and UTF-8 by Tom Scott on Computerphile [9m 36s].

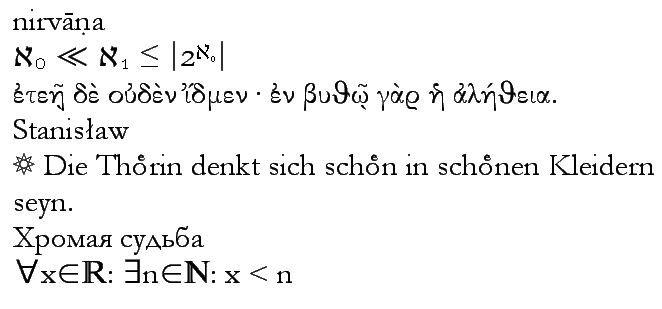

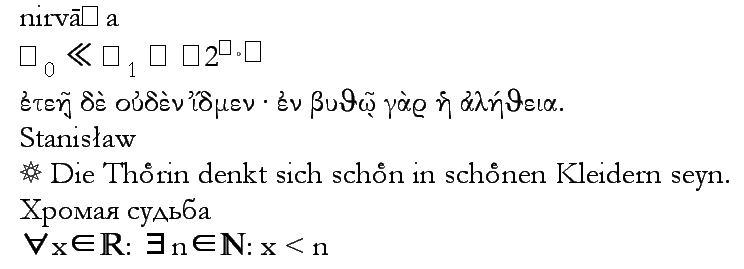

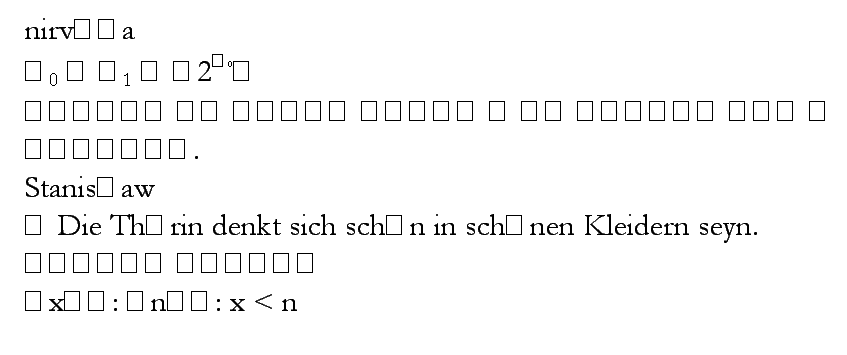

Nowadays, Unicode works just about everywhere, and almost all new content uses it. There is still an occasional problem of whether or not your computer has the correct fonts installed that contain all the characters you need. Sometimes you will see a box show up in place of an unsupported character. The figures show same text displayed on three different systems.

rob_pike on Twitter