Python language

Install Python 2.7

You can skip this section if you are using a lab computer with Python already installed. Otherwise, here are your choices:

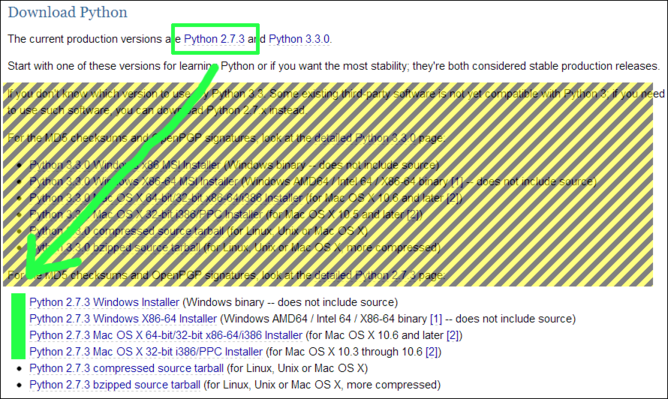

Download Python 2.7.x from the Python web site (not version 3.y.z!), as shown in the rest of this section

Use Python directly in your browser with PythonAnywhere – I have described how to get it working in this short video.

You may be able to use the Python app for the iPad – let me know how it works!

The rest of this section is about installing Python 2.7 on your computer.

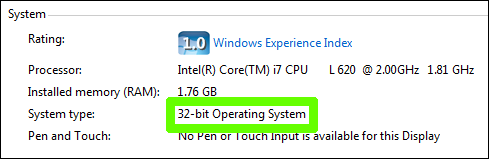

To choose the right installer, you need to select between Mac and Windows, as well as between 32 and 64-bit. If you’re not sure about the machine word size, from the Windows start menu you can choose Control Panel » System and Security » System, and look for the System type.

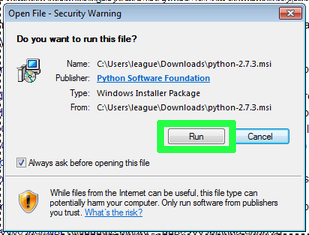

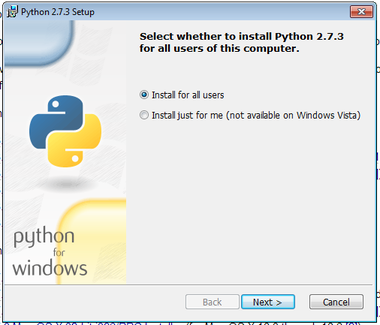

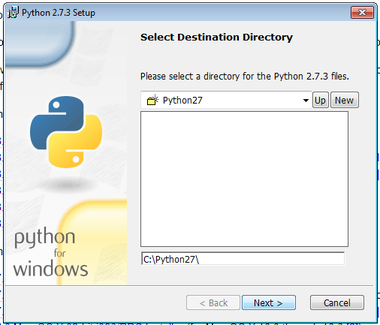

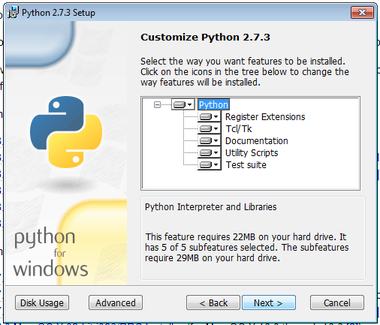

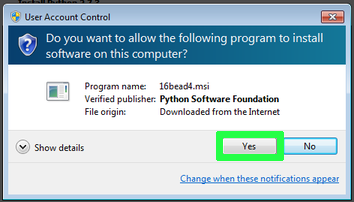

The install process is entirely straightforward, just work your way through the steps. I’ll illustrate them below, but you probably won’t need it.

Start your program

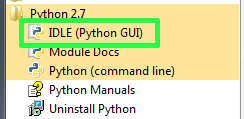

From the Windows Start menu, select Python 2.7 » IDLE (Python GUI). There will be a similarly named program in /Applications/Python 2.7 on the Mac.

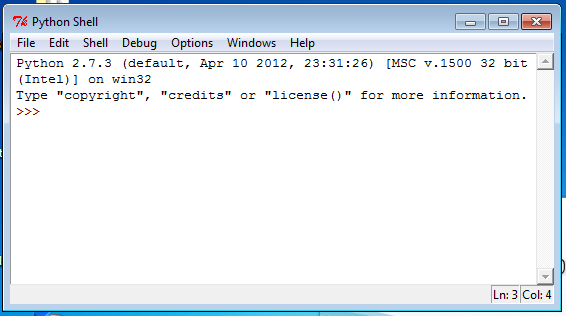

A window called the “Python Shell” will appear. It displays a prompt like “

>>>”. This is the window in which you will interact with your program.

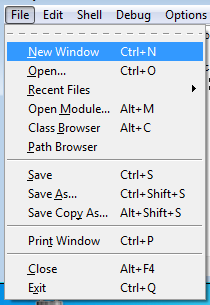

You need a second window, in which you will type and save the content of your program. Select File » New Window from the menu.

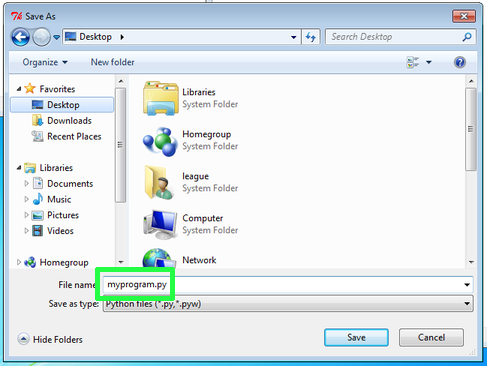

While in the new window, select File » Save and give it a filename that ends with

.py(this will enable syntax coloring). You can also choose the folder to save it in, such as your Documents or Desktop folder.

Type your code into the

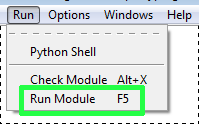

.pyfile, and save it with File » Save, or Ctrl-S or ⌘-S.Use Run » Run Module (F5) to run it, and interact with the program in the Shell window.

Printing messages

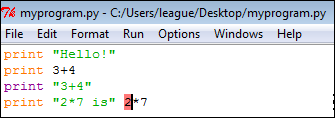

Here is a program you can try that prints messages on the screen. You can copy and paste this block into your .py file, then save and run. (Note: the coloring used on this web page may not precisely match the colors you see in IDLE.)

print "Hello!"

print 3+4

print "3+4"

print "2*7 is", 2*7When you run this program, the Shell window will contain:

>>> ====================== RESTART ======================

>>>

Hello!

7

3+4

2*7 is 14

>>> The double quotes indicate a string of characters (text). That portion is output exactly as written. Any portion not in quotes is interpreted by Python. Thus the difference between printing 3+4 (which produces 7) and printing "3+4".

Fixing errors

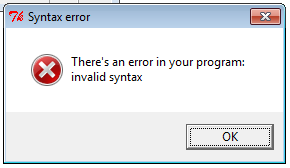

The most common error you will see is probably “Invalid syntax”. It pops up like this:

Dismiss that message, and you see it also highlights a portion of your program in red.

Often the red part is just after the source of the actual error. In this case, we omitted the comma between the two different things in the print statement on that line.

Another kind of error shows up in the Shell window. It might look like this:

Traceback (most recent call last): File "C:/Users/league/Desktop/myprogram.py", line 4, inprint "2*7 is", x NameError: name 'x' is not defined

The actual error is the last line. This one is called a NameError. But the Traceback section can help you too, by telling you which line number to examine (in this case, line 4).

Doing calculations

We can store variables very simply in Python by using an equals sign. Variable names consist of a sequence of letters, numbers, and underscores (no spaces), but they cannot start with a number. Here are examples of valid variable names:

quiz3the_last_dayFrankx

These are not valid:

quiz 32nd_quiz

Variable names are case-sensitive, so x and X are both valid, but they are not the same variable. Below is a program that uses variables to perform a computation.

quiz1 = 32

quiz2 = 40

quiz3 = 16

average = (quiz1 + quiz2 + quiz3) / 3.0

print "Average is", averageWhen you run it, the output should look something like this:

>>> ====================== RESTART ======================

>>>

Average is 29.3333333333Python (and most languages) distinguish between numbers that are integers (whole numbers), and numbers that can contain decimal points. The latter are called floating-point numbers. When you divide two integers, Python performs integer division, which eliminates any remainder. You can overcome this by including a decimal point in your numeral, even if it’s just 3.0 – that forces it to be represented as floating-point.

>>> 9/2

4

>>> 3/4

0

>>> 9/2.0

4.5

>>> 3.0/4

0.75Getting input

Python has a very handy built-in function for receiving input from the user of your program. It works like this:

name = raw_input("Enter your name: ")On the left side of the equal sign is a variable name. On the right side is the raw_input function. In the parentheses, you specify a string that will be the prompt presented to the user. When you run the above program, it looks like this:

>>> ====================== RESTART ======================

>>>

Enter your name: You are expected to type something at this point, and press enter. Whatever string you type will be placed into the variable name. Here’s a more complete sample program:

name = raw_input("Enter your name: ")

print "Welcome to my program,", name

year = int(raw_input("What year were you born? "))

age = 2013 - year

print "You are", age, "years old."Running the program looks like the following. The parts the user types are indicated by «angle quotes».

>>> ====================== RESTART ======================

>>>

Enter your name: «Chris»

Welcome to my program, Chris

What year were you born? «1988»

You are 25 years old.Boolean expressions

Python has values for Booleans – they are called True and False. Note that, like variable names, they are case-sensitive, so you must capitalize them as shown. There are also operators that produce Boolean values. The most obvious ones are for numeric comparisons. Consider this transcript in the Python shell:

>>> 3 < 5

True

>>> 3 > 5

False

>>> 2 < 2

False

>>> 2 <= 2

TrueThe last example in that block is <=, pronounced “less than or equal.” There is also >= for “greater than or equal.” You cannot have a space between the two operators: < = will be a syntax error.

Checking whether two things are exactly the same is a little tricky. The equals sign = is already used to mean variable assignment, as in:

my_quiz_score = 38This statement above does not ask whether my_quiz_score is equal to the value 38. Instead, it sets the value of that variable to 38, and whatever value it had previously is lost.

In order to ask the question, whether a variable is equal to a certain value, you need to use a double equal sign: ==, like this:

>>> my_quiz_score == 38

True

>>> 38 == my_quiz_score

True

>>> 21 == my_quiz_score

False

>>> 19 == 19

True

>>> 19 == 21

False

>>> "nice" == "evil"

False

>>> "nice" == "nice"

TrueCompound Booleans

Python also has operators from Boolean logic; they are called and, or, not. Here are a few examples involving them:

>>> 3 > 5 or 5 < 6 # becomes False or True, which is True

True

>>> 3 > 5 and 5 < 6 # becomes False and True, which is False

False

>>> not True

False

>>> not (3 > 5)

True

>>> my_quiz_score >= 0 and my_quiz_score <= 40

TrueThat last example determines whether the value of my_quiz_score is within a certain range: from zero to forty, inclusive.

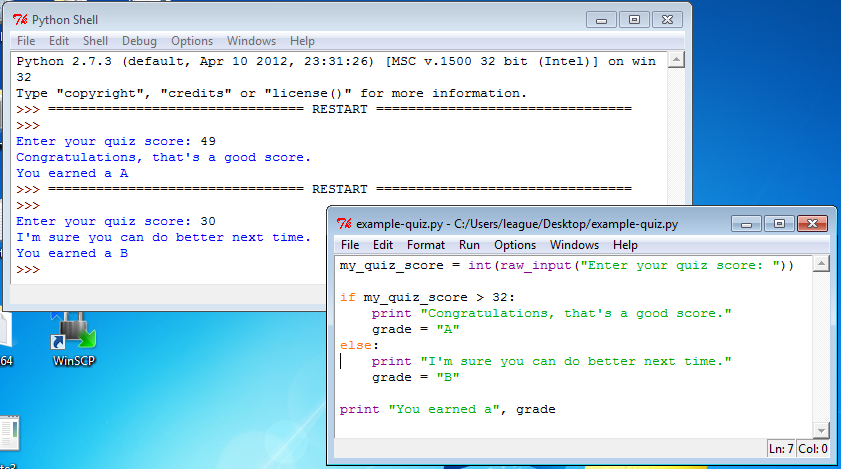

Conditional statement

Now that we’ve seen Boolean expressions, we’re ready to explore conditional statements. You remember these from working with pseudo-code; they were statements like:

If X > 0 then output X and stop.The syntax in Python is a bit more regimented. There is a keyword if (must be lower case), and then the Boolean expression, followed by a colon (:) – it’s a very common mistake to forget the colon!

On the next line, and indented a few spaces, you put any statements that should be executed only if the condition is true. Here is an example:

if my_quiz_score > 32:

print "Congratulations, that's a good score."

grade = "A"

print "Thanks for taking the course."You can see that the last print statement in that block is not indented. That means it is no longer controlled by the if. If we reach this code when the value of my_quiz_score is 38, the output will be:

Congratulations, that's a good score.

Thanks for taking the course.And the variable grade will contain the text string "A". On the other hand, if my_quiz_score is 31, the output will be only the last line:

Thanks for taking the course.It’s also possible to provide an else block that executes when the if block doesn’t. Here’s a complete program you can paste into the Python program window and run with F5:

When you run it, try entering different values at the prompt in the shell window, and observe the results.

If/else chain

It’s a fairly common pattern to “chain together” a series of if/else conditions, something like this:

if my_quiz_score > 32:

grade = "A"

else:

if my_quiz_score > 24:

grade = "B"

else:

if my_quiz_score > 16:

grade = "C"

else:

grade = "D"You can see that the indentation increases each time an if is embedded within the else of another if. Try tracing this code with my_quiz_score set to different values, to see what ends up being stored in grade. You may even want to revise the previous program using this technique, so it can output more than just A or B.

This chain is common enough that Python provides a shortcut for it so that the continued indentation doesn’t get out of hand. The shortcut relies on the keyword elif, and it looks like this:

if my_quiz_score > 32:

grade = "A"

elif my_quiz_score > 24:

grade = "B"

elif my_quiz_score > 16:

grade = "C"

else:

grade = "D"This program does the same thing as the previous one, but it’s a little cleaner and shorter.

Exercises

These are helpful exercises, to test putting it all together. First, create a program that does the following:

Enter quiz 1 score: «90»

Enter quiz 2 score: «80»

Your average is 85.0

Your grade is BIt can just use 90/80/70/60 as the thresholds for A/B/C/D. Once you have that working, try this one:

Enter quiz 1 score: «60»

Enter quiz 2 score: «95»

Enter quiz 3 score: «92»

Dropping the 60

Your average is 93.5

Your grade is AIt will ask for three scores, but then drop the lowest one before computing the average of the other two.

Reopening your programs

Once you have saved your .py file, it may not work just to double-click your file again to reopen it. That will run the program in a console window, which is especially awkward because it might not pause to show the output before the window disappears.

Instead, you can right-click in the .py file and select “Edit with IDLE” (if on Windows). Or simply open IDLE first and then use the File » Open menu and navigate to the .py file from there.