Notes from 10/5

Feedback on how it’s going

Slow down!

Confusion about type signatures

It seems like the GitLab forum is really helpful for those who use it; check it out!

Function composition

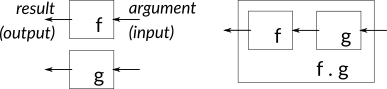

Functional programming uses several different operators for combining functions in different ways. The simplest is the compose operator, whose syntax is just a dot (period), surrounded by spaces. Here is the mathematical notation, followed by the Haskell notation:

\[(f\circ g) (x) = f(g(x))\]

(f . g) x == f (g x)The diagram shows how the two functions are composed, with the output of the right one leading to the input of the left.

Function composition

Here are some examples with function composition:

ghci> twice x = 2*x

ghci> square x = x*x

ghci> (twice . square) 5

50

ghci> (square . twice) 5

100It can be a little surprising that this works right-to-left, but it’s the tradition in the mathematical notation. Another functional language, Elm, uses << for this right-to-left composition, and >> for left-to-right. We can of course define these operators in Haskell too:

ghci> (>>) = flip (.)

ghci> (square >> twice) 5

50

ghci> (twice >> square) 5

100We used the built-in flip function to reverse the order of the arguments to the compose operator (.).

With partial application

Composition can get a little more interesting when the pieces we’re gluing together are themselves the result of partial applications. So here’s a function with two arguments that we can partially apply:

ghci> f x y = 2*x + 3*y

ghci> g = f 5

ghci> g 7

31

ghci> g 9

37And here’s a composition:

ghci> (f 5 . f 6 . f 7) 8

388To convince ourselves that this result is correct, we can work through a typical derivation, like:

(f 5 . f 6 . f 7) 8 == (Peel off the right-most function)

(f 5 . f 6) (f 7 8) == (Substitute definition of f)

(f 5 . f 6) (2*7 + 3*8) == (Arithmetic)

(f 5 . f 6) 38 == (Repeat)

f 5 (f 6 38) ==

f 5 (2*6 + 3*38) ==

f 5 126 ==

2*5 + 3*126 ==

388With monadic functions

In the assignment 4, we used a different kind of composition operator: (>=>). This is for composing functions that produce monadic values, for example, Maybe values. So applied to Maybe, each function in the pipeline has the option of producing Nothing, in which case that is just returned. If it produces Just, then the value is sent to the next function.

There is also a version (<=<) that does right-to-left composition, more like the standard (.) operator. To use either of these, you need an import declaration. Below are some examples. We’ll define a half function that only works on even numbers; and then a square that refuses to multiply if the number is too large!

import Control.Monadghci> half x = if even x then Just (x `div` 2) else Nothing

ghci> square x = if x > 100 then Nothing else Just (x*x)

ghci> (half >=> square) 20

Just 100

ghci> (half >=> square) 240 // square returns Nothing

Nothing

ghci> (half >=> square) 9 // half returns Nothing

NothingAssignment 4 solutions

The complete A4 solutions have been posted. In class, we spent a little more time on isEmpty and isFull, which I defined this way:

isFull :: BoundedStack a -> Bool

isFull (BoundedStack cap _) = cap <= 0

isEmpty :: BoundedStack a -> Bool

isEmpty (BoundedStack _ []) = True

isEmpty (BoundedStack _ (_:_)) = FalseFullness is based only on the capacity; we don’t care about what elements are in the stack. On the other side, emptiness is based only on the elements: they are either the empty list, or there’s at least one element (but we don’t care what it is).

Interestingly, after presenting this in class, I looked at the implementation I wrote previously, and found that I approached them quite differently. Rather than using the BoundedStack constructor to pattern-match, I used the field names capacity and elements, and then composed them! (null is a Boolean function on lists that returns True if the list is empty.)

isFull :: BoundedStack a -> Bool

isFull = (<= 0) . capacity

isEmpty :: BoundedStack a -> Bool

isEmpty = null . elementsMonoids

We previously learned about Functor, which has an fmap. If Functor describes something that is “mappable”, then Monoid describes something that is “appendable”. To use Monoids, we need an import:

import Data.MonoidA type can be a Monoid if it supports two basic operations:

ghci> :i Monoid

class Monoid a where

mempty :: a

mappend :: a -> a -> amemptyproduces a value of the type that represents nothing, such as an empty list orNothing.mappendtakes two values of the type and combines them together to make a new value that somehow includes both.

List monoid

The simplest demonstration of a Monoid is the list type, where mempty is the empty list, and mappend is the list concatenation operator (++).

ghci> mempty :: [Int]

[]

ghci> mappend [1..5] [6..9]

[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]Like any function with two parameters, you can use mappend infix or there’s an operator (<>) that is equivalent:

ghci> [1..5] `mappend` [6..9]

[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]

ghci> [1..5] <> [6..9]

[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]

ghci> "Hello" <> "World"

"HelloWorld"There is also a third operation in Monoid, derivable from the other two: mconcat takes a list of elements and appends all of them together in sequence:

ghci> mconcat ["Alice", "Bob", "Charlie"]

"AliceBobCharlie"Tuple monoid

So that’s pretty simple for lists (including strings), but what about other types? A tuple is a monoid if its element types are monoids. For example, here is mappend (aka (<>)) applied to a tuples of strings:

ghci> ("Alice", "Bob") <> ("Jones", "Smith")

("AliceJones","BobSmith")

ghci> ("Alice", "Bob", "Carol") <> ("Jones", "Smith", "Patel")

("AliceJones","BobSmith","CarolPatel")Question: What is mempty when instantiated to a pair of strings?

Maybe monoid

The Maybe type is also a monoid, if its element type is a monoid. The mempty of course is Nothing. And then mappend essentially joins the Just values, ignoring cases where it finds Nothing.

ghci> mempty :: Maybe [Int]

Nothing

ghci> mappend (Just [1..4]) (Just [2..8])

Just [1,2,3,4,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]

ghci> mappend (Just [1..4]) Nothing

Just [1,2,3,4]

ghci> mappend Nothing (Just [1..4])

Just [1,2,3,4]

ghci> mappend Nothing Nothing

Nothing

ghci> mconcat [Just "Alice", Nothing, Just "Bob", Just "Carol", Nothing]

Just "AliceBobCarol"Defining a tree monoid

Can we define a Monoid instance for a tree? Previously we made a tree data type where both the branches and leaves carried values, of different types. That is a little difficult to reconcile with the expectations of Monoid, because there was no such thing as a completely empty tree.

So let’s design a different kind of tree. In this one, Leaf is just an empty constructor, with no value attached at all. Values can be stored at branches. Since each of the left and right subtrees can be an empty Leaf, our branches essentially can have zero, one, or two children. (And if there’s one child, we can distinguish whether it’s a left child or a right child.)

data Tree a

= Leaf

| Branch { value :: a, left, right :: Tree a }

deriving (Show)Here are a couple of sample trees:

sample1 :: Tree String

sample1 =

Branch "A"

(Branch "K"

(Branch "M"

Leaf

(Branch "Q" Leaf Leaf))

(Branch "P" Leaf Leaf))

Leafsample2 :: Tree String

sample2 =

Branch "B"

(Branch "S"

Leaf

(Branch "C"

(Branch "D" Leaf Leaf)

(Branch "F" Leaf Leaf)))

(Branch "R" Leaf Leaf)It’s helpful if we can print these out in some way. Here’s a set of functions I wrote to do some crude ASCII representation of the trees.

prettyPrint :: Show a => String -> Tree a -> String

prettyPrint indent Leaf = indent ++ "- *\n"

prettyPrint indent (Branch v Leaf Leaf) =

indent ++ "- " ++ show v ++ "\n"

prettyPrint indent (Branch v l r) =

indent ++ "- " ++ show v ++ "\n" ++ prettyPrint tab l ++ prettyPrint tab r

where tab = indent ++ " |"printTree :: Show a => Tree a -> IO ()

printTree = putStrLn . prettyPrint ""Their output:

ghci> printTree sample1

- "A"

|- "K"

| |- "M"

| | |- *

| | |- "Q"

| |- "P"

|- *

ghci> printTree sample2

- "B"

|- "S"

| |- *

| |- "C"

| | |- "D"

| | |- "F"

|- "R"The * shows the position of an empty Leaf, but if both children are empty leaves we just omit them. The lines and dashes make it pretty easy to see the parent-child relationships in the trees, but here “left” is interpreted as top and “right” as bottom.

What would it mean to append two trees? One way to define it is to require that the value types are also monoids, and then we merge together corresponding branches in the tree structure. In these examples, the roots A and B would merge into AB. Their left children would merge into KS. The first tree’s root doesn’t have a right child, so the result would use the right child of the second tree. Here’s the definition of a Monoid instance:

instance Monoid a => Monoid (Tree a) where

mempty = Leaf

mappend Leaf Leaf = Leaf

mappend Leaf br = br

mappend br Leaf = br

mappend (Branch v1 l1 r1) (Branch v2 l2 r2) =

Branch (mappend v1 v2)

(mappend l1 l2)

(mappend r1 r2)In the final case – appending two branches – the (mappend v1 v2) looks like a recursive call, but it really isn’t. That’s because it’s being used at a different type. So if the tree contains string values, it is appending the strings. When mappend is applied to the left and right subtrees, that definitely is recursive.

Here is the result on our two trees, first in one direction:

ghci> printTree (sample1 <> sample2)

- "AB"

|- "KS"

| |- "M"

| | |- *

| | |- "Q"

| |- "PC"

| | |- "D"

| | |- "F"

|- "R"and then the other:

ghci> printTree (sample2 <> sample1)

- "BA"

|- "SK"

| |- "M"

| | |- *

| | |- "Q"

| |- "CP"

| | |- "D"

| | |- "F"

|- "R"Or you can join a tree with itself:

ghci> printTree (sample1 <> sample1)

- "AA"

|- "KK"

| |- "MM"

| | |- *

| | |- "QQ"

| |- "PP"

|- *Main program

I’m not using this for anything, but if you compile this with runghc, it requires a main, so here it is.

main = return ()